Regret

A review of ‘Tasmanian Aboriginies - A history since 1803’ 2012 by Lyndall Ryan. Personal reflections and implications for Ecoconnections.

Why I read this book

I read this book because I am Tasmanian. I had a sense that the stories I had grown up with were incomplete and possibly wrong. I was aware of significant controversy and that my own attitude might need adjusting. My personal story and family farming heritage weave into Tasmania’s Aboriginal history. I read this book to be clearer on how this thread was drawn and how it could be.

In the late 1980’s I lived with (Cape Barren) islander descendants of Tasmanian Aboriginies at the Poimena hostel for country kids in Launceston Tasmania. This experience gave me affection and a sense that these people are very special in the world. We were all shy, curious country kids on one level but the islanders also had, I think, a special sense of family, the islands and the sea with gentleness and kindness. We were also all boisterous late teenagers, separated from our families, jostling with finding our place in the big city of Launceston (population 65,000). Some of the Cape Barren Islanders were younger 12-15 where most of us were 16 and 17. These fleeting friendships left a sense of happy privilege touched with curious melancholy for the cultural richness these friends represent. We were each seeking to make our way in the world. So it was not an environment where we could understand much of what ‘islander’ heritage meant.

Ryan’s book is the work of an academic and practical historian. She faces controversies and denials head-on with a careful synthesis of relevant data, stories of people and historical documentation. It is well referenced.

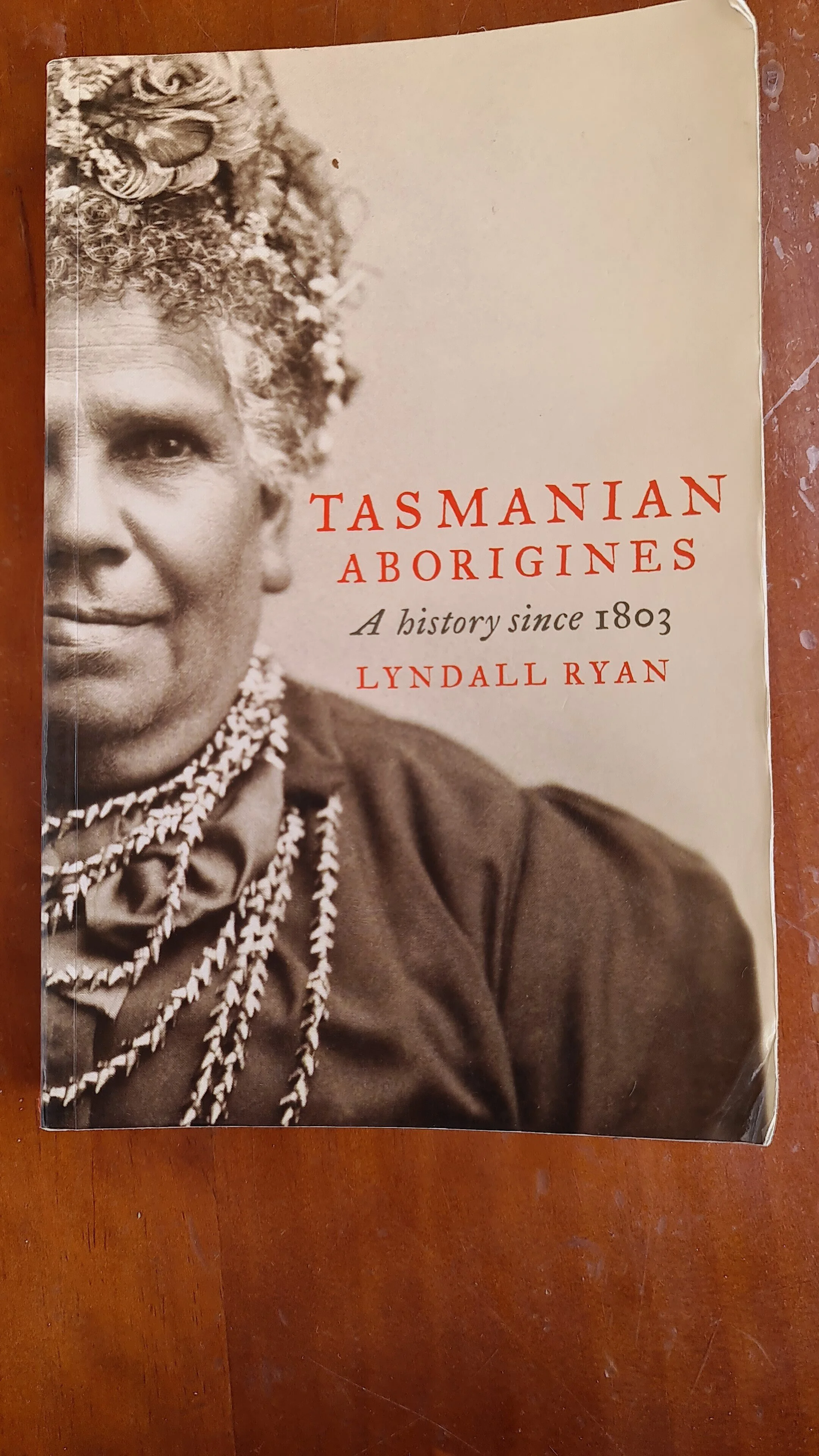

Front cover image of Fanny Cochrane-Smith, late 1800’s

The story of the Tasmanian Aboriginals

Ryan divides the story into Invasion, War, Surrender, Incarceration Survival and Resurgence. I’ll abbreviate it for you below.

Tasmania was settled by the British in 1803 as a Penal colony. The Aboriginal population of 100 clans of 40 to 50 people divided into 9 nations spoke at least one of four major languages. Ryan cites sources estimating a total population between 3,000 and 10,000. My own synthesis of this evidence settles on a working figure of 7,000.

The dominant approach to the aboriginal population was hostile. When I say dominant that is not to say that people were not aware of the tragedy unfolding. It is that these sentiments, including from Governor Arthur, were not sufficient, capable or willing to combat the strong socioeconomic imperative of the settlers. Massacres, settlers shooting on sight, martial law, removal of hunting grounds and disease saw the population effectively removed from the main island of Tasmania by 1835. Ryan documents the ‘Invasion’ and ‘War’ in its harrowing detail. For example, the ‘Black War’ period (1823-1834) saw 201 Colonists killed and an estimated 878 Aboriginies. Ryan tells detail of the characters and geography involved as a synthesis of available evidence. By 1835 the population of Tasmanian Aboriginies numbered hundreds. Reading Ryan I get a sense of the scale and nature of this truth which is often (sensibly) shielded from the historical stories you might learn as a child.

George Augustus Robinson is an important character in this story. He was active in Tasmania from 1824 to 1839. He learnt aboriginal languages, as Governor Arthur’s agent, negotiated surrenders, served as superintendent at Wybalena (Flinders Island) and introduced Spanish Flu from Sydney. His diaries are an important source.

Ryan describes a period of ‘Incarceration’ from 1835 to 1905. In 1835, 112 Aboriginies were removed to Wybalena on Flinders Island. In 1847, 47 Aboriginies relocated to Oyster Cove. In 1905 Aboriginal woman Fanny Cochrane-Smith died in Hobart. The remains of these last of the full-blooded Tasmanian Aboriginies were sought after by bone collectors around the world. William Lanney, introduced in 1868 to Prince Albert, the Duke of Edinburgh as ‘King of the Tasmanians’, “the last man of his race”, died in 1869. The story of how his body parts were stolen and distributed around the world, including his head to the School of Anatomy at the University of Edinburgh, is truly macabre.

I will not retell the stories of the individual people, of tribal leaders. Ryan draws out these stories as a faithful historian, making geographies and characters clear, sufficiently to get a sense of the individuals and the circumstances of their attrition. The individual tragedies often made me gasp and is a great strength of the book. The richness of the sense of regret from the sum of these stories is a reason to read the book. I feel I was in sure hands with Ryan and now have a firm grasp on what happened. The emotional response is my own.

The chapters on Survival and Resurgence show resistance to assimilation; a fight for land and recognition; and strengthening community affiliation. There are particular low points and high points in the relationship with the Tasmanian Government. The fact that descendants of the Tasmanian Aboriginies currently form a vibrant and active community is a hopeful and positive contrast to this overwhelmingly tragic story.

Tasmanian Aboriginies, Totems and Ecoconnections

There is a little in this book about totems. “…customs were based on totems (each clan…taking a designated species of bird or animal)”[p7]. This is a sufficient lead for me to be interested in finding out more. Ryan’s book has a helpful cultural overview however is not a detailed exploration of how these customs worked.

The place of totems in an overview like this is interesting for Ecoconnections. Totems seem to operate in the background as a base layer of understanding. Daily activity around a family fire, building shelters, finding food, managing territory and sexual relations occupy more of Ryan’s description. I can imagine however totems played a larger part in dance, song, art, and stories; things that explore meaning in relationships between one another and life in the landscape. I feel like Ecoconnections is on track with a connection that mostly sits in the back of a persons mind with occasional opportunities to explore what the species means in its landscape relationships.

What can Tasmanian Aboriginies teach us about Land Management?

There are some clues about what the Tasmanians Aboriginies can teach us about living as a part of the Tasmanian ecology. The knowledge that they did live for many thousands of years as a part of Tasmania is an important starting point. I would contend that they had a highly functional system using totems as indicator species as an aid in observing and managing the landscape dynamics. If we say this system was high functioning and productive we can see that this is no security or defence against a stronger invader or outside economic force.

Land management practices employed include fire-stick farming. Wild harvest of rangeland macropods was a feature. Fish traps, eggs and mutton birding were managed within sustainable harvest limits. The cultivation of yams, seeds and greens are not detailed in this book, nor are the techniques for the care of ‘native bread’ fungi. This is an illustration that cultivation techniques and land management practices are seldom well documented in the peer-reviewed or historical literature. History that considered warriors, battles and political events skim over the long development times for unique expressions of geography in terms of food flavour and style. Knowing these techniques is an opportunity lost.

Regret

The knowledge that Tasmanian Aboriginies lived for many thousands of years as a part of Tasmania the island and were almost completely destroyed gives me a deep sense of regret. This is the regret of an opportunity lost. The harrowing stories, of invasion and war the injustices, the struggle through surrender, incarceration, survival and now to resurgence are important inputs to an emotional response. The opportunity lost however is the most regrettable. This is in the opportunity to understand the foods they produced and how. It’s the opportunity to know their land management practices and how culture helped them manage landscape functions. But most importantly it’s the missed opportunity for friendship with the Tasmanian Aboriginies; and through this, for friendship with the Tasmanian Landscape, carefully working together to build landscape productivity and functionality as habitat for rich and ancient biodiversity.

PostScript on the unstoppable enterprise of farmers and settlers.

John Lock in Chapter V of his second treatise on government (1689) contends that nature on its own provides little of value to society, implying that the labour expended in the creation of goods, gives them their value. This underlies the idea that farmers were creating value in settling Tasmania. This idea also legitimised settler conquest of North American native lands. Agricultural expansion in Western Australia’s Fitzroy River is part of the same sentiment. I have visited the Chitwan National Park in Nepal on the North Indian plain. Enterprising farmers here occupy all available land unless prevented by an armed force on the park border. I’m sure there are similar places in Africa.

Farming is important to feed a human population. However, it is not the only value. Biodiversity is important. Functional indigenous managed systems are important. There are significant improvements in regenerative agriculture and overall agricultural productivity that can take some pressure off biodiversity.

What do we know of the quality of the soul of a farmer? Tending productive plants and animals, rugged independence, hard work, enterprise, production and a relationship with the land shape the positive character of farmers. Farmers are involved in killing animals. Farmers are involved in mechanically forcing the landscape to do things. Farmers are often self-interested. In the case of the Tasmanian settlers to the point of the bloody demise of the local population and the destruction of a functioning ecosystem.

Totemic systems seem to be more a characteristic of indigenous, more mobile peoples and less a character of settled people. There is perhaps a basic constitutional divide. On the one hand, there are people who have a totemic sense of the dynamics of the landscape and the creatures in it. On the other, there are enterprising settlers of John Lock’s sentiment with enterprising, mechanical mindsets to reshape nature to be productive. Outside this frame, many people do not consider their effects on the landscape. There are also landscapes that have no deliberate human management. In any case relationships with the landscape and other species can be strong components of the spiritual constitution of a person.

The branches of my own family, that I know, arrived in Tasmania in 1857 and thereabouts with a strong sense of enterprise, farming enterprise. Whilst this is after the periods of the ‘Black War’ slaughters I am troubled that the sentiment may be the same. This does not lead me to abandon the spirit of farming enterprise, rather change its purpose. The purpose of agricultural productivity is for me, now, to leave room for other creatures. Land managers, now, have a higher purpose, build the biological functionality of the landscape and be as productive as possible, to leave room for other peoples and creatures. Many rural and urban land managers still work to profit as the principal purpose of their activity.

Many development agencies see prosperity and private property as inextricably linked with the security of private property being key to economic development. With this view, the rush to secure private land property is increasing across the world. Sentiment that allows the interests of indigenous peoples, the landscape as a whole and other species to be considered will need to operate in parallel with a system of private ownership. Ecoconnections are one force that can allow other species to be considered by voters and consumers in this system.